Covers

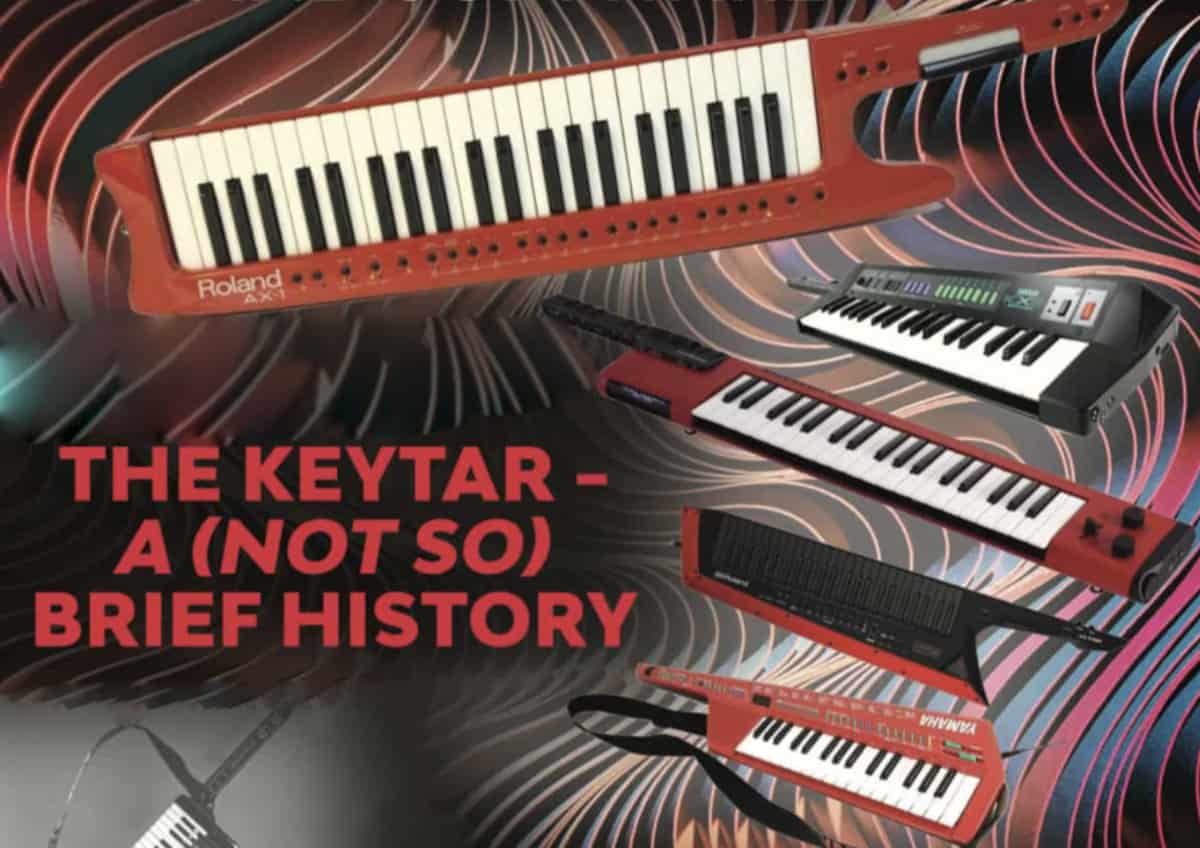

A (Not So) Brief History of Keytars

Because it’s not fair that only guitar and bass players can have onstage get-togethers. Mark Jenkins traces these popular strap-ons through the ages.

Keytars – keyboards that can be worn strapped round the neck like a guitar – have a long and (let’s face it) troubled history. They’ve been the subject of some derision over the years, but keep popping up in new models and varieties, so they must have some continuing appeal to keyboardists of all varieties.

Anthropologists disagree as to when the keytar was invented, but you may want to go all the way back to the Portative Organ, a small hand-pumped pipe organ (sounding more like a set of whistles) known from medieval times for its portability Catalina Vicens is one modern exponent.

From 1966, Mustad AB of Sweden offered the Tubon and it was played very early in the career of Kraftwerk – the electronic instrument has a long tubular body and a short set of keys. In the early 1970’s Edgar Winter slung on a lightweight Univox electric piano by adding a guitar strap, and later used the independent keyboard of an ARP 2600 synth, as heard on “Frankenstein.”

Not long after its launch in 1970, though, someone thought to separate and strap on the keyboard from a MiniMoog, played this way by Jan Hammer, Gary Wright, and Steve Porcaro among others. Hammer not only wore the keyboard like a guitar, but he made the synth sound like a guitar (primarily by playing it through a guitar amp) and worked hard on making his pitch bend technique sound highly guitar-like also.

On albums such as “Black Sheep,” Hammer made the keytar sound fabulous as a lead instrument, and he worked on developing several new models such as the Probe, which could select new synth sounds remotely.

Hillwood meanwhile had developed Edgar Winter’s portable electric piano approach with the lightweight Rockeyboard, a piano with a filter, while George Mattson launched Syntar, more along the lines of a portable analog synth. In the jazz realm, both George Duke and Herbie Hancock played the Clavitar, while a later development of Jan Hammer’s Probe was played by Roger Powell, famous for his work as an ARP endorsee and with Todd Rundgren’s Utopia.

Two approaches to the keytar had emerged – either the sounds were created onboard, in which case you had to connect audio to an amp or mixer, or they weren’t, in which case you had to connect via a control cable to some other audio source.

The Moog Liberation, introduced in 1980, offered the worst of both worlds. It did have sounds onboard, but it had to be wired to a 19 inch rackmounted base station, both to send its audio (and CV/gate to control other analog synths) and to get its power. This meant using a very specialized cable and facing disaster if this was lost or damaged.

Also, the Liberation, comprising basically a Moog Rogue monophonic synth plus a big chunk of wood painted usually black but sometimes white, was extremely heavy, and very demanding to play for long periods. Despite this it saw use by Devo, Rick Wakeman with Yes, Jean Michel Jarre, and many others, and there are some great Liberation solos on Jarre’s album “The China Concerts.”

All these designs were fairly specialized and costly, so in the 1980’s a few other approaches to keytar design were tried out by different manufacturers. Dynacord didn’t make synthesizers but had a sampled drum sound system and built this into the Rhythm Stick, a guitar-style drum sound controller.

Meanwhile Roland’s affordable SH101 analog synth, which was very light and portable, appeared with an optional modulation grip (and in a range of colors: grey, red, or blue). The stubby handgrip controller didn’t leave the synth looking very sleek and streamlined, nor could the SH101 exactly produce screaming leadlines, but it did represent the cheapest way to get into portable synthesis.

These days Behringer’s MS1 clone of the instrument (again in various colors) offers exactly the same keytar possibilities but with MIDI.

Keytar design really took off with the development of MIDI and associated modules, making the connection method to a remote keyboard much more obvious and straightforward. Just before MIDI appeared, Dave Smith of Sequential offered a short remote keyboard for the Prophet 5, and for a change this not only looked professional but could control a full set of monophonic, polyphonic, and potentially screaming sounds. Dave Stewart was one prominent user in his duo with Barbara Gaskin.

In the following year, 1983, Yamaha went the full MIDI route with the KX1 (offering full-size keys) and KX5 (offering mini keys). Depending on the physical size of the player, either of these could look highly professional and impressive.

The KX1 was not manufactured in great numbers, but the KX5 became quite popular and is still collectable today. It has great expressive controllers and a respectable medium-size layout, which means it doesn’t dwarf the player.

At the time, Yamaha was offering FM digital sounds from the DX range of synths, so most KX players matched up their keytars with this type of sound source, sometimes with added guitar distortion (Chick Corea was a notable example).

Using analog sound sources, though, such as the contemporary MIDI-equipped Prophet 600, might have been much more effective. Tim Blake and Jean Michel Jarre played the KX5 very effectively, and Jarre also had a custom wood-paneled keytar instrument built by the guitar makers Lag.

Incidentally, Yamaha had an odd one-off entry into the keytar field a year earlier. The CS01 (Model 1 in grey or later Mk 2 in black and green, or black and gold) was a lightweight monophonic analog synth with a speaker, part of a range of compact studio equipment. It came with guitar strap locks so could easily be strapped on, and could be used with a breath controller, which gave amazing expressive possibilities. Patrick Moraz was one player who found no difficulty overcoming the instrument’s miniature keys, and the CS01 in either version remains sought after today.

A couple of other small synths at the time were equipped with strap locks – notably the full size key Korg Poly 800 and the mini key Casio CZ101 – but neither of these looked particularly sleek for keytar purposes, nor had the cutting sounds they would ideally need.

No, the future of keytars lay with MIDI output, plus a connection to whatever synth or module you fancied taking on stage. With patch changing, good expressive controls, and 30-foot MIDI cables all becoming readily available, the keytar became a real on-stage proposition.

In 1984/5/6 Lync launched the LN1, a sleek and professional instrument with the look of the Powell Probe (later LN1000 and LN4), Roland launched the AXIS in silver with a distinctive double-braced controller arm, Casio launched the AZ1 in pearly white, and Korg launched the RK100 in black or red. All these were pure MIDI controllers that would sound like whatever synth you connected them to.

Since that time, Korg and Roland continued updating their keytar designs, while Yamaha and others dropped out of the field. The race then was to get high quality sounds on board the keytar (given battery power, you could then use a guitar transmitter and go totally cable-free). Roland’s AX1 and later AX7 didn’t do so, Korg’s battery operable FM synthesis 707 keyboard (in white, blue, or black) did, but had a stubby not very guitar-like shape.

Yamaha’s battery-powered SHS10 and SHS200 did get sounds on board, though these were 2-operator FM synth sounds and very weak. But both instruments had MIDI output, so while they looked a little toy-like (having mini keys coming in grey, red, white and rarely black) they could be matched with modules which sounded as professional as you liked. The red SHS10R in particular remains sought after and can fetch a couple of hundred dollars (or pounds, or Euros).

During this period there were some stunning keytar performances to be seen. Rick Wakeman became a specialist in playing them at blazing speed (often duetting with his son Adam). There are amazing clips on YouTube, for example from his concerts in Cuba, where he walks into the audience playing a Roland keytar – then gives it to an audience member to hold while he continues to thrash away on it.

But some (including those who never liked them in the first place) got the impression that the keytar had gone away, and from Roland’s point of view there was indeed a gap in production until nearly the end of the decade. And then the AX-Synth put in an appearance, getting right up to date with high quality onboard sounds, MIDI and USB, and followed a year later by the AX-09 Lucina, a stripped down version intended more for entry level users and fun players.

The Lucina, with it cutout control arm design, looked a little odd compared to other keytars, but had decent preset synths sounds for leads, pads, and basses. After a period of being highly collectable, it’s now changing hands at affordable prices (the black sparkle version being a little more highly valued than the more common white model).

Roland’s current pro model is the AX-Edge, a large and rather spiky design with customizable color front panel “blades” and even more powerful (editable) onboard sounds, while Korg’s response was more or less to tack a guitar controller arm onto the virtual analog MicroKorg synth in the RK-100S (later with a wooden body model too). All these synths with onboard sounds could be matched with a guitar transmitter, so at least you no longer needed any audio output cable.

Alesis entered the keytar field with two generations of the battery-powered Vortex (in white or black), which went truly remote with a Bluetooth dongle (claiming a range of 400 feet) plus a software suite offering powerful leadline and textural sounds. So that meant you weren’t tied to anything at all on stage – except having to run a laptop (the instruments had MIDI as well, if you didn’t mind running a MIDI cable).

The Vortex is a great controller – including an accelerometer sensor so you can use movement as a modulation source – and the instrument is still available including through Amazon.

That about summarizes the keytar field at the moment, with less than a handful of professional level models in production, a handful of cheap and cheerful alternatives, and a busy second-user market among those who want to get into portable performance. There are also some keytar-like toy keyboards, and many custom one-off projects from various musicians around the world.

Note that MIDI-equipped keytars or those with onboard sounds may well have non-portable uses around the studio too, though if they have protruberant controller arms they tend to be not as compact as they may at first appear.

There are super-cheap alternatives too (let’s face it, there are quite a lot of instruments you could screw a couple of guitar strap locks into, all Yamaha ReFace synths, and the Arturia Keystep come to mind). Look too for the discontinued Rock Band 3 game keyboard, they’re actually great miniature MIDI keyboards with battery power, patch selection, and a controller strip. Or note the suggestive guitar strap locks on your Behringer UMA25S MIDI controller keyboard…

While stars like Lady Gaga have recently become great keytar exponents – sometimes using custom-built examples – sadly the most recent entries into the keytar field have been among the least successful.

Yamaha launched a lightweight instrument to run their Vocaloid vocal synthesis software, but since this approach only seemed popular in Japan, developed two keytar instruments from the same body shape, the Sonogenic SHS500 and SHS300.

These instruments unfortunately fell between almost every stool imaginable. The Sonogenic instruments were pleasingly lightweight, but looked stubbornly toy-like whether in white, black, or blue. These were aimed at entry level musicians, but were extremely expensive on release.

They had onboard sounds, but the sounds were terrible – only a handful of them (12 on the SHS300), and sounding worse than the 2-operator FM sounds of years before. Both instruments use Bluetooth and USB to help run play-along software called Chord Tracker. But while this is intended for entry level players, it’s extremely complex to set up and run. The best thing that can be said about these instruments is that they are available much more cheaply now.

So the keytar may have taken a mis-step lately, but it’s bound to return before long in one form or another. Wherever there are keyboard players who feel unfairly hidden behind their stacks of instruments, wherever there are guitarists who think they have no competition at center stage, wherever there are players who want to get the girls (or guys) regardless of their possibly more nerdy choice of career instrument… there will the keytar be. So play on!