Books

Five Spectacular Synth Books

Mark Jenkins reports on some remarkable new books about electronic music

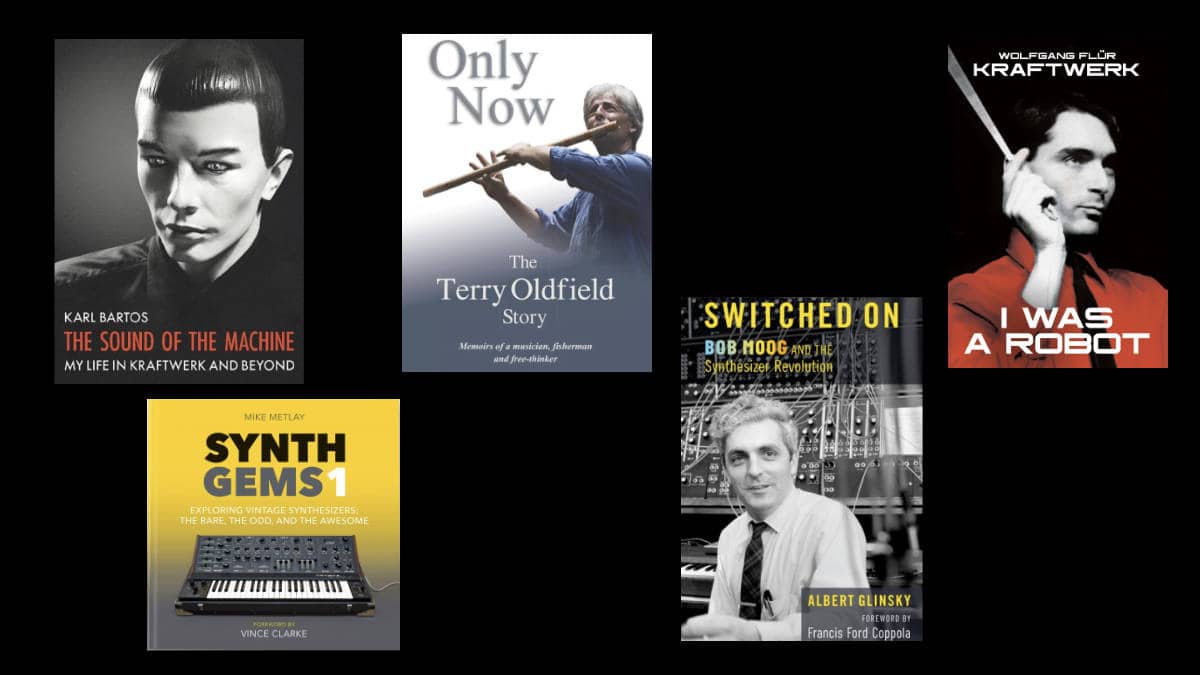

While download reading is still popular, there are plenty of reasons to own a real book. “Synth Gems 1” by Mike Metlay (Bjooks, £83.68 in the UK) is one of them.

Clearly it’s a labor of love, arriving packed with corner protectors like a piece of Ikea furniture. At 320 full color pages (hardback) it’s a substantial product, compiled and researched around the world.

Metlay, who has experience as a nuclear physicist as well as in the role of writer and magazine editor, is equally fascinated by excellent instruments, rare instruments, and outright quirky instruments. The nearly 50 instruments covered in detail range from the MiniMoog (1970) to the Alesis Andromeda (2000).

Vince Clarke provides a foreword, rhapsodizing on some less likely favorite instruments such as the compact Casio CZ101, and the other contributors show an equal affinity for their subject – mainly, given the time frame, comprising analog synths, though digital and sampling instruments such as the tiny Casio VL1 and the massive Fairlight CMI get equal coverage.

Much of the photography was carried out by the staff of EMEAPP, though SMEM (the Swiss Museum of Electronic Music) and a private collection called Synthorama also contributed. And the photography is superb.

Though there are showings of museum setups, most of the pictures are of individual instruments on plain colored backgrounds and in pin sharp focus, allowing the reader to see every knob and label. Publisher and founder Kim Bjorn, who oversaw the overall design and production, has done a superb job.

You’ll read about Ensoniq’s first product the ESQ1, the very obscure Jeremy Lord Skywave, the beautiful Gleeman Pentaphonic Clear in translucent perspex, and the frankly ugly Murom Aelita from Russia – don’t worry, you’ll never find one of those. (Metlay, though, describes it as “packing an enormous punch.”).

Many of the instruments are depicted in huge 2-page spreads (yes, like what we used to refer to as centerfolds) and there are supplementary features including a list of museums and collections where you can see many of these enticing instruments in the flesh.

The book closes with the Alesis Andromeda of the year 2000, but does promise more to come with a teaser of the Hohner/Cavagnolo Prolog, a synth so obscure that it’s not clear whether anyone knows how to make it work – yet.

Bjooks.com publications are available through all major book outlets, but the company itself offers a very swift international mail order service.

Detailed autobiographies from electronic musicians are few and far between, but “The Sound of the Machine: My Life In Kraftwerk And Beyond” by Karl Bartos has proven popular in German. It has just become available in an English edition from OmnibusPress.com, which in hardback form is again a mighty chunk at 634 pages, including two sections of color and black and white photos.

Yet it sells very inexpensively at under $30 (£20 or less in the UK).

The Bartos book will inevitably be compared to Wolfgang Flur’s earlier “I Was A Robot,” also available through Omnibus (around £13 in the UK) and well worth a read. That one had a troubled history, with the core members of Kraftwerk objecting to some passages and (I believe) some photos, which they felt trivialized their background history.

Re-edited and released in English, Flur’s book remains a fascinating read, and he turns the tables in this “Extended Edition” by inserting some history of all the legal arguments about the first version.

The book has a loose, informal style that emphasizes the human concerns behind the so-called Man-Machine. Flur, who left the group in 1987, also provides plenty of detail about his subsequent solo projects such as Yamo, and includes black and white pictures both of this period and of the Kraftwerk days, during which he appeared on albums from Autobahn to Electric Cafe.

There’s an interesting backstage photo from 1975 showing the “Percussion Cage,” a motion-sensitive device that not many people saw, since it didn’t work all that well.

The Karl Bartos book takes a fractionally more formal approach, aided in this by a superb translation from Katy Derbyshire. Transliterating German dry humor is one thing, but doing so in a manner that reads flowingly is another. In this translation we appreciate everything Bartos was thinking, and whether he took matters quite seriously or not…

One interesting concern is the great deal of work he did as a classical percussionist, even overlapping with the “Autobahn” tour (he wasn’t on that album, but started work from “Radio-Activity”). In fact a classical marimbaphone was an early Kraftwerk instrument on stage, clearly shown in some photos, but that didn’t last long. Soon the band ditched the last vestiges of conventional instrumentation and went all-electronic.

Bartos in fact supplies a satisfying amount of technical detail on how this process proceeded. There’s not a vast amount of detail on instrumentation, but he does explain how and when a particular sequencer was adopted, which instruments he had in his own studio setup, and so on – a good balance of the technical with the personal.

“The Sound of The Machine” is a great read, though it does have something of a sense of impending doom over the first, say, 400 pages. As all fans of the band know, increasing periods opened up from one album to the next, and the band founders Ralf Hutter and Florian Schneider always regarded themselves as the core members.

Even early in the book, discussing gifts from the record labels and the relative opulence of hotel rooms makes it clear that the “classic” 4-piece lineup wasn’t going to last forever, and there remain questions about exactly who did what on which album…

Like Flur, Karl Bartos had mixed emotions on leaving the band. “It’s hard to describe my mental state after saying farewell to Kraftwerk. I certainly didn’t take the split lightly. I was hurt and disappointed – but at the same time I was euphoric.”

There’s plenty of detail on his post-Kraftwerk solo and collaborative work, and some excellent photos. And, in a personal comment not directly derived from the book, I can say this: after leaving the band, Karl Bartos seemed well able to create wonderful songs in the “classic” Kraftwerk style like “Fifteen Minutes of Fame” while the “core members” did not – which seems odd, really.

Less potentially contentious is Albert Glinsky’s superb biography “Switched On – Bob Moog and the Synthesizer Revolution” (around £24 in the UK). This is a massive work of research aided by documentation directly from the family (both Bob’s widow Ileana Grams-Moog and daughter Michelle Moog-Koussa), even down to the level of individual invoices to and from the Moog company in its early years.

And this is very much a history of Bob Moog as businessman and innovator, rather than electronics engineer. The book is for those who want to understand Bob Moog the man, not the Moog Modular system.

There’s plenty of history of the Moog family, to the days when Bob started building Theremins and eventually launched his voltage controlled module designs, and a comprehensive explanation of who else was involved.

You’ll meet characters like Herb Deutsch, who sadly passed away as I was reading the book, and who gave the main marketing push to the early Moog products; and Bill Waytena, who left the company, came back to re-finance it as Moog Musonics, bringing in the Sonic 6 design, then left again.

What’s remarkable is the detail given on the exact difficulties experienced in launching and running the Moog company, which never quite seemed to make as much as it spent; the last-minute nature of many promotions, with modular systems being wired together through the night just in time for pioneering live concerts; and the great deal of competition met in the early years.

There was no certainty at all that Moog would maintain a leading role in synthesizer production in the face of ARP and Oberheim, or before long, the Japanese.

Meanwhile, Bob took time hand-crafting guitars, designing his own circular house, and objecting strongly to the launch of the MiniMoog. This era-defining synth launched in 1970 would not exist had employees not built a batch of ten in secret while Bob was away on business.

The book has two chunky sections of black and white and color photos, the former mainly of the Moog family, the latter covering magazine advertising, Moog players like Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson, and much more.

And while the technical detail on instruments thins out considerably towards the end of the book – though the Moog Sanctuary, a short-run version of the MemoryMoog for churches, and the last-ditch SL8 prototype are mentioned – it must be remembered that the title is “…and the synthesizer revolution.”

By the time Bob Moog sadly passed away in 2005, the revolution had well and truly succeeded.

So if you want intricate details of the difference between a MicroMoog and a MultiMoog, or a list of PCB revisions of the Moog modular filter, this is not the book for you. But if you want a fascinating insight into Moog the man, it has never been bettered. Published by Oxford University Press (oup.com) 471 pages hardback.

Finally to “Only Now – The Terry Oldfield Story” (self-published autobiography, 408 pages, around £12 softcover, £18 hard cover in the UK, www.terryoldfield.com). This is sub-titled “Memoirs of a musician, fisherman and free-thinker.”

While I can’t comment knowledgeably on any fishing content, I do know the musician as brother to Mike Oldfield of “Tubular Bells” fame and a superb wind instrument player, working mainly in the area of what is probably still referred to as New Age music. Their sister Sally, a very successful singer in her own right, provides an introduction to the book.

Terry played basic guitar with a young Mike, but first became interested in the flute while living in Greece. He developed a style that was useful on some of the early Mike Oldfield albums (and played in the London live premiere of “Tubular Bells”), but rapidly made a name for himself performing more tranquil, atmospheric music that aligned with his spiritual beliefs.

Certainly those beliefs had been forged through adversity, including a spell working in an Australian copper mine, two divorces, and more recently losing an eye to a melanoma.

As Terry’s instrumental playing and composing developed, he found a steady stream of work for TV documentaries, and was quickly picked up by New World, at the time the UK’s leading label for relaxing instrumental music. His layers of flute (and later other instruments such as bamboo flutes and whistles) over simple keyboard parts became immensely popular.

Eventually the workload caused a collapse due to stress – and around the same period brother Mike needed support for a recurring crisis of confidence.

The success of the “tranquil” releases through New World led Terry to cut down on producing TV music and to travel the world looking for inspiration for new albums. Living in Australia in 2005, he went through a divorce and a collapse in his album sales thanks to the rise of downloading.

But a new partner, Soraya, introduced him to yoga and Eastern-influenced music, and by 2016 they were releasing albums together such as “Namaste.” Included are black and white photos from this period, as well as much earlier family photos.

I’ll leave the rest of Terry’s history until the present day to readers. “Only Now” is, in truth, a story of adversity overcome, of a developing spirituality, and of a journey through music. And there is, indeed, some fishing.

All books available from the publishers, bookstores and/or Amazon