DAW

7.2 Steps To Heaven: Dolby ATMOS and Apple Spatial Audio

What are these ballyhooed 3D audio formats all about?

Intro

Q: What is Dolby ATMOS?

A: Dolby ATMOS is an encode/decode process that introduces a novel concept to surround mixing. It’s a departure from the classic channel-based surround models: 5.1 or 7.1, with .1 being a subwoofer and the first number specifying the number of channels.

So 5.1 is two front speakers, a center, two rear surrounds, and a sub. 7.1 adds two speakers on the sides.

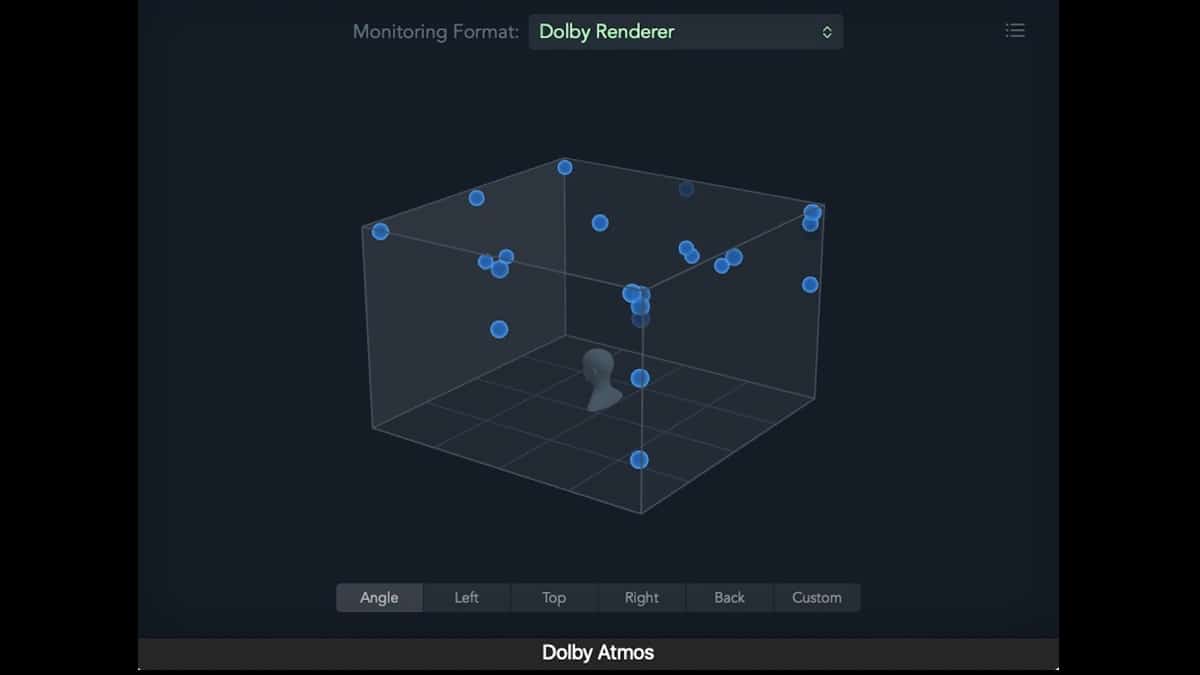

Instead of the classic channel-based surround models, ATMOS allows for signal routed to ceiling speakers (the .2 in 7.1.2) and these new things called “objects.”

Objects can move anywhere in the virtual space around the listener, and are not “locked” to specific speaker channels. The speaker array (whether a movie theater, art installation, Apple AirPods Pro, or ATMOS mixing studio) then engages certain speakers based on where that “object” is placed in the virtual space.

Q: What is Spatial Audio

A: Spatial Audio is Apple’s term for this kind of channel/object, which is now fully integrated into Logic Pro 10.7 and higher. The latest update, Logic Pro 10.7.3, includes two types of rendering for surround mixes: Dolby ATMOS, and Apple Spatial Audio.

Q: Is that all there is to Spatial Audio – a proprietary name?

A: No. Spatial Audio can also position sounds in a 2-speaker headphone mix. It uses DSP to simulate moving objects around the 3D soundfield, including overhead.

Q: So you don’t need 7.1.2 speakers to mix in Spatial Audio?

A: Actual surround coming from speakers is obviously more effective. But Spatial Audio works on any stereo headphones.

The difference with compatible headphones is that they also track your head movements. If you turn your head to the left or up, for example, you’ll hear the sound get louder in the left rear or overhead.

Q: What headphones are compatible with Spatial Audio

A: According to Apple’s site, to get the full ATMOS experience on Apple Music you need a pair of AirPods Pro, AirPods (3rd generation), Beats Fit Pro, or AirPods Max.

Logic 10.7.3 allows for monitoring a mix with these devices as well, which means creating an ATMOS mix, as it will likely be heard by consumers, can be done without a big 7.1.2 speaker array. And there was much rejoicing.

***

“C’mon! It’s the current year!” as “the kids these days” say when wondering how stereo could “still be a thing?!” (That’s a tongue-in-cheek characterization of the music business’ marketing efforts to popularize spatial audio.)

Musicians have been prodded into venturing into the new surround frontier, often encountering the derision of their peers. For example, check out this response from music industry blogger Bob Lefsetz to one of his readers.

(Spoiler alert: Bob hates old songs with new spatial audio mixes).

Regardless of one’s opinions of those participants (one of whom was a Nashville engineer tasked with remixing the catalog of a major label into ATMOS), it highlights the fact that there is a lack of consensus as to the best practices.

For Synth and Software readers destined to our fate in this new world, what can we do to make sure our music doesn’t sound like crap in spatial audio?

One interesting development for projects that are just music, not movie scores or games, is musicians can count on recent statistics that estimate 80% of music consumed by adolescents is through headphones or earbuds.

Until recently, mixing Dolby ATMOS or spatial audio mixes required a minimum 7.1.2 speaker setup. This is no longer the case, as the ATMOS/spatial renderers offer binaural (2-channel) monitoring. That means for the native spatial/ATMOS renderers in the various DAWs, their headphone monitoring modes may be sufficient (if not preferable) when used by mixers and musicians.

If it is in fact the case that the next generation is consuming music primarily through headphones or earbuds, and the streaming services (Apple, Tidal, etc.) are all opting for playback in spatial audio/ATMOS, then creating/mixing in spatial audio on headphones is probably a good idea. These developments also open the spatial audio door to smaller studios and “laptop producers.”

As it concerns Synth and Software viewers, spatial audio offers new modes of artistic expression. This new mode concerns how sounds move through, or are placed in the virtual space.

As with any art form, there are some guidelines emerging to help achieve good results. One of those guidelines covers the relationship between movement, timbre, and frequency. Just like a mixer might remove some muddiness by carving out competing frequencies between a kick drum and a bass guitar, or filtering out low rumble from a spot mic on a violin section, the frequencies can greatly determine the clarity of sound as it moves around the space in a spatial audio mix.

Simply put, the higher the frequency the easier it is for the human ear to determine its precise location of a sound source in the spatial audio mix (until you get to about 10kHz). Think of the placement of a subwoofer in a home theater system – low frequencies sort of fill up the room and are more difficult to pinpoint. A mosquito buzzing around your head? It is remarkably easy to determine which ear it is closest to, even if flying behind you.

If the intent is to have sounds or instruments moving around the listener, know that it is a lot easier to localize sounds with higher frequencies (if clarity is your goal of course). High strings or synths, high guitar solos, shakers, tambourines, piccolo flutes, high piano keys, all are more easily heard when moving than low instruments.

Percussion elements like shakers or tambourines that move around are especially easy for the listener to track. The complexity and density of their upper harmonic content lends itself in this way when moving around the space.

Another guideline is that similar to panning in stereo mixes, movement will attract the ear a bit. So the levels of a sound in motion may need some automation compared to when it is static.

These initial guidelines about moving sounds through the space beg an important question: when should things move? Of course, there are many possibilities but one approach that is becoming more common is that the movement of sounds follow the form of the song or composition.

On a pre chorus, sounds may begin to move closer, or higher, and then “jump” to their next position when that chorus hits. Perhaps an à cappella track begins at a distance, and as the piece progresses, the voices get closer and closer until they fade away in the distance at the end.

The point is, that the movement of those sounds should be tethered to a musical reason, just like a mixer might bump the guitars a dB or two on a chorus.

Boiled down to the basic question, just as a music musician might ask “what notes,” “which instrument,” “how fast,” “who is singing,” they should now also ask “where is the voice,” “where is the oboe,” “where should the synth ARP start and end?”

Next, the type of signal, mono/stereo, needs some explanation as it relates to movement and placement around the listener. Mono signals are easily routed to “objects,” which are the basis of the ATMOS mixing system.

Stereo signals are routed to pairs of objects (one per channel). Because the initial stereo signal has width, a musician/mixer will observe that the exact location is more difficult to hear than a strictly mono signal. Here are two approaches that illustrate how to handle mono/stereo sources.

A stereo pair of objects can be placed in the front high corners of the ATMOS environment box around the listener overhead, and pass over the listener ending in the back corners. Listeners will hear a wide sound passing over them.

For a mono signal with mid/high pitch content, that may start center in front of the listener. As it passes over, it will be perceived as a sound with a precise location.

In the first example, because of its wide nature, a big epic synth might be an appropriate sound for a wide sound that washes overhead. The mono signal might be a mono vocal delay, each echo being heard in its precise location as it passes overhead.

In each case, the sound/signal fits the objective. Big wash = widely-spaced stereo pair of objects. Little vocal delays = mono object sailing overhead.

There is a common ATMOS mixing technique that doesn’t always translate to “good” or “cool” in my humble opinion. That is the “inside the instrument” effect. A plurality of ATMOS and spatial audio mixes take an approach where multi-mic setups of single instruments are placed all around the environment.

An example I have heard many times is putting drum microphones 360° around the listener. Overheads behind the listener, cymbals high, top snare mic high up, bottom snare mic down low, cymbals hard left/right, etc. This can be cool, but it can also be distracting from more important elements.

I have tried this many times with multi-mic solo piano recordings. When the microphones are placed all around the listener, it feels like you are inside the piano. Ultimately, if the goal is a realistic impression of a solo piano concert, the microphones are positioned in front of the listener, with maybe a pair of outriggers behind the listener.

Then a 7.1.2 reverb is added to fill the space. Very nice results can be produced this way.This is a good segue into creating the impression of a room with an ATMOS mix. Much of this is done the traditional way, with nice surround reverbs locked to specific channels, delays, and the like. Consider sending delays to dedicated objects.

For sample libraries with multiple mic positions, this might be a good place to start.

Lastly, it is worth covering the “size” of an object. When the size of an object in ATMOS is increased, two things happen: the precise location is more difficult to discern, and there is a perceived gain increase.

It is difficult to describe without hearing it, but be sure to run your own experiments when toying with this parameter. The sound becomes big and “smeared,” which can be a nice effect. (Side-chained object size EDM producers? Yes please!)

Caution: all of the objects in your mix with their sizes increased can reduce the clarity quite a bit and sound bad.

ATMOS and spatial audio still are the “Wild West” of music, but it is time musicians and mixers begin to standardize some best practices. If there is one consistent principle that has guided engineers, mixers, songwriters, and composers since the dawn of recorded music, it is that the music should guide the technical and creative choices – lest we find ourselves on the receiving end of a Lefsetz letter… or worse!