Features

Max Mathews and Me

Memories of the founding father of computer-based music.

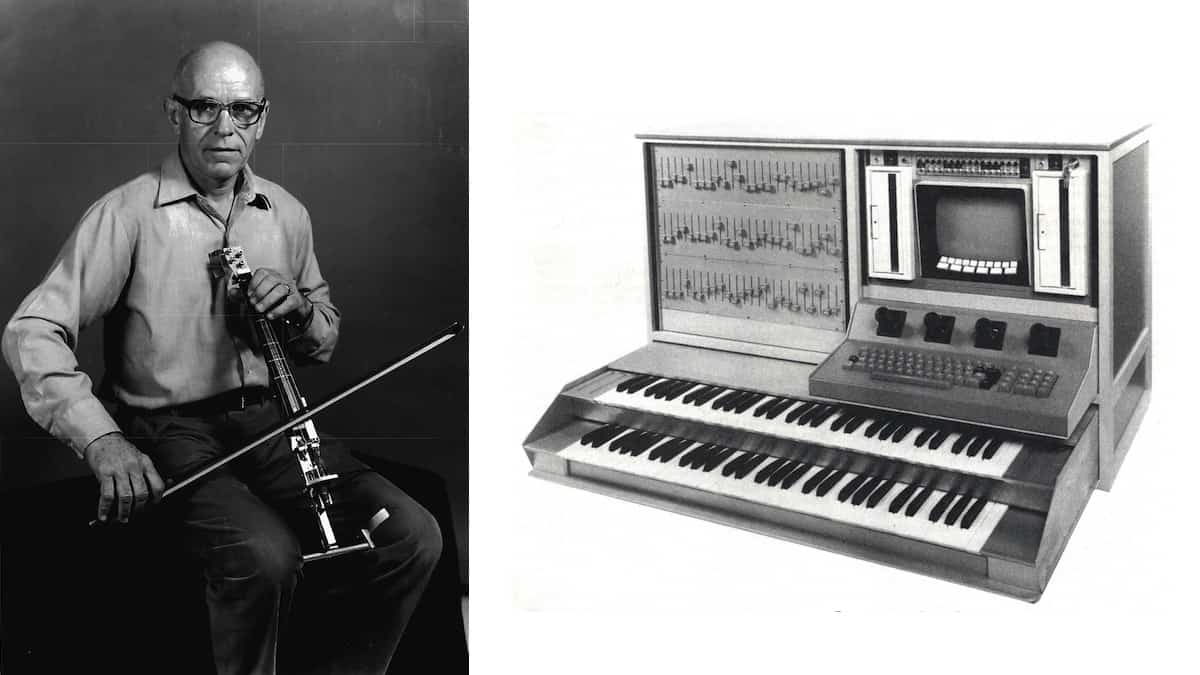

Max Vernon Mathews (born November 13, 1926; died April 21, 2011) was the Bell Labs scientist who invented computer music in 1957. He wrote the first computer music score program (forerunner of today’s CSound), built the first computer-controlled analog synthesizer (the GROOVE system), and pioneered new interfaces for live computer music performance (including the Radio Baton).

My first memories of Max were in the summer of 1962. As a shy and reclusive 9-year-old, I was holding on to a rope for dear life in the bow of his sailboat as we traveled across Long Island Sound. In the stiff breeze, I looked up to him with a sense of awe and wonder. I was already a huge fan, because in the fall of 1961, my father had brought home a test pressing of Music from Mathematics, a collection of short pieces made with the first computer music program at Bell Telephone Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey, a place I grew up calling, “the Labs.”

My father was a mathematician at the Labs and was part of the group that created this record. I played the test pressing so many times that I wore it flat. We had to buy the commercial record when it was released the following year to replace the record I had ruined in my youthful enthusiasm. I can remember the impact of hearing those little sound experiments on that record. The following year, I built my own synthesizer to pursue my own electronic sounds. Since that time, I have never stopped building electronic circuits and playing electronic music.

Human Control of Computer Instruments

My next time with Max was during the summer of my senior year, July and August of 1971. He hired me to work as a wiring technician in the computer music output room of the GROOVE system. This was the first assemblage of voltage-controlled sound modules to be controlled by computer. I was building fixed-tuned resonance circuits based on the exciting revolutionary new op-amp of the time, the U741. Using these circuits, Max was designing the first prototype of his electronic violin emulating the timbre of a Stradivarius. This was a great place to be. I became fascinated with psychoacoustics.

Jean-Claude Risset, a French composer who later became head of IRCAM at the Centre Pompidou, was in residence at the Labs that summer, and I admired his Music V composition “Little Boy Suite.” Risset used Music V to generalize the pitch illusion described in Roger Shepard’s 1964 paper, “Circularity in Judgments of Relative Pitch.” Risset programmed a continuous sound whose pitch went down and down forever. These later came to be called Shepard tones. (You can generate one yourself from a VST plug-in)

Max presided over this hotbed of activity and enjoyed the interplay of all of the creative personalities. His electric violin was his pride and joy. Playing with the real time controls of the GROOVE output gave him the idea for what later became his famous Radio Baton.

I spent the next eight years living and working in Honolulu, Hawaii. Starting in 1972, I taught classes in ARP Synthesizers. We at Sinergia Studio were a stocking and demonstrating ARP dealer. I also ran a testing station for the ARPANET, a Department of Defense project that was the first iteration of the internet. The group of engineers I worked for, calling themselves the ALOHA project, helped develop TCP/IP, the protocol used on today’s internet.

Secret Midnight Arts Culture at Bell Labs

In 1979, Max invited me to come back to Bell Labs as an “artist in residence” after I had sent him my first commercial electronic music synthesizer release, Electronic Music from the Rainbow Isle. I doubt that Max ever listened to it; his musical ear, like my father’s musical ear, was fashioned from tin. Nonetheless, they both played and loved music. I joined a special group of people who created art during the 3rd shift, past midnight at the Labs.

Max needed someone with my music and programming background for a special situation at the Labs. In 1977, hardware engineer Hal Alles and software engineer Doug Bayer put together a remarkable musical instrument known as the Alles Machine (aka the Bell Labs Digital Synthesizer, or Alice), which pushed the then-known boundaries of digital signal processing and sound generation. They learned what they could and showed the machine around. After two years, it became a bit of an embarrassment. It was obviously a musical instrument, and they had spent a fair bit of money on it, even by the profligate Bell Labs standards of the day. By the summer of ‘79, they pulled the support plug and moved the machine upstairs from Hal’s lab to Max’s little cubbyhole computer music lab in room 2D529, nestled in the back corner of the corridor and safely out of sight.

Max brought me in to see what could possibly be done with the machine in terms of actual music. Max had a real interest and appreciation of music. He paid me a small weekly stipend ($117, as I recall) with petty cash vouchers from his secretary, and he gave me a Resident Visitor’s pass to the Labs.

I did what I could to be helpful and useful to him and the other scientists in the Acoustics & Behavioral Research department. I recall making soundtracks for several Bell Labs publicity films. For the most part, I simply had free run of his lab and the other facilities at Bell Labs. Once again, it was a great place to be. Wonderful and accomplished musicians such as Larry Fast, Roger Powell, and Laurie Spiegel would come by and record pieces on the Alles Machine for their albums. I spent a great afternoon talking with Bob Moog, showing him the Alles Machine’s software implementation.

Sequential Permutations

At that time, I had a lucky break. A young engineer named Greg Sims worked in Hal’s lab and was about my age. Starting in 1976, I had become fascinated with aleatoric music composition techniques and started playing with sequential permutations using the EML 400/401 analog sequencer. I bent Greg’s ear about all this. He was kind enough and interested enough to program a three-stage sequential permutation algorithm using three of the bottom programmable sliders on the Alles Machine. I was in absolute heaven!

Greg discovered that he had a congenital tumor in his stomach. It was already untreatable when it was discovered. He had to leave the Labs and, to my enduring sorrow, he died a few short months later. At that time I discovered something about Max that I’ve found to be true with many engineers. Max was not comfortable talking about emotions or feelings. He had feelings, but they just were not part of his vocabulary. Science, engineering, and machines were things he understood. People were far more difficult.

The Alles Machine finally fell into ruin in the spring of ‘82. I left the Labs. I remember an evening at Max’s home a few years later. Jean-Claude Risset was back in town, and Max had gathered a bunch of computer musicians for an evening soirée. His wife Marjorie boiled hot dogs, which we cut up into small pieces and ate with toothpicks. My parents were there, since they were friends with the Mathews. Jean-Claude went around to each person with unfailing courtesy and charm and asked each one about his or her work, which meant their work in computer music. I remember watching and hearing the intense, prideful competition. Each person tried to make themselves and their work seem as important as possible.

I didn’t say a word. I never thought my work or my passionate interests had much significance. In a world filled with pain and sorrow, it seemed like a highly elitist affectation, something to keep quiet about. I could not bother a disinterested world with such obscure concerns. Max, as usual, was utterly oblivious to this. He was now focused on real-time Max Mathews’ happiness control of complex musical processes. Since I was always a live performer, I thought this was great. We had a good talk, and I could really relate to his current interests.

An Exceptional Life with Good Karma

In the fall of 1993, I saw Max for the last time. He was now retired from the Labs and a music professor at CCRMA (the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, pronounced like the word, karma), part of the music department at Stanford University. I was on tour with my musical group Electric Diamond, with Stuart Diamond on Lyricon and Karen Bentley on violin. Max allowed me to arrange a concert at CCRMA. We had a grand space with four huge loudspeakers. We played our synthesizer version of “Pictures at an Exhibition” along with some improvs. Max looked noticeably older, but it was like we had never parted company. He seemed happier than he had been at Bell Labs, because he didn’t have to manage people. He could play with his machines in the company of many very bright people who knew him and understood his passions. Max could really see where things were going, and he was glad to still be a part of it all.

I wish Max could have seen today’s graphics tablets. He would have loved the amazing musical instruments that now use all the tablet’s position and motion sensors, creating exceptional musical effects. From the time I was 7 years old to the present day, Max’s work, instruments, patronage, and encouragement have shaped my life in music. I am truly grateful to have known him.