Artist News

How to Design Sounds Like a Film Composer

Movie and TV composer Michael Whalen reveals his approach to developing sounds for music.

I’ve been creating sounds for more than 40 years. I coax them out of analog and digital synthesizers, samplers, and all manner of digital workstations. I process noises I grab from the real world on little digital recorders or on my phone. I make sounds with my mouth, my body, and various kitchen and garage implements. I fabricate textures I produce on guitars, basses, and electronic wind instruments, even though I play neither guitar nor reeds. Because I’ve created tens of thousands of sounds that adorn countless commercials, television shows, films, and records and for live performance, I am confident in my own theory of sound design, which I will share with you now.

There Are Two Types of Sound

1) The sounds you are trying to emulate

2) Everything else

Let’s concentrate on sounds you’re trying to emulate, whether they’re musical instruments or sound effects. When you play them, ask yourself, do listeners hear what you intend them to hear? If listeners still wonder what they’re hearing seconds after your sound starts playing, then you’ve failed to emulate the sound you intended.

Whenever deciphering a musical sound interferes with a listener’s enjoyment, you should consider it an unsuccessful application of sound design. You never want the musical sounds you make to mask the music. Successful sounds add color, texture, and sonic weight to your compositions, but they must always be transparent to the listener’s musical experience.

That’s a tall order. Making sounds that are musical and not just noise for noise’s sake is a skill that can take years to perfect. The wonderful sounds you hear on an album may not be spectacularly complex; the artist may have simply created the right context for those sounds to shine.

In many cases, less is more. Stacking a musical part with multiple sounds doesn’t always enhance that part. In fact, it can have an adverse effect if similar frequencies stack up and cancel each other out. Let your finished sounds breathe by featuring them; in other words, don’t allow other sounds to mask the impact of sounds you’ve designed. Too many people spend time carefully crafting a texture or patch, only to bury it within a track that’s too dense. Being disciplined about how and where to use sounds is the sign of a talented sound designer.

Impressionism or Realism?

Being great at emulating sounds means you’re exceptional at capturing the smallest details of the sounds you aim to reproduce. What details, you might ask? Well, let’s create something like a flute sound. You might think, “I just dial up some filtered square waves, and I’m good to go.”

Wait a second—what kind of flute are you emulating? When you add up all the traditional Western classical flutes and ethnic flutes from other countries and cultures around the world, hundreds of options are in the flute family. Each one of those flutes has different sound qualities—different amounts of air, pitch shift, harmonic effects, and even key clicks.

As you think about creating sounds, consider your depth of detail, as if you’re painting with sound. Ask yourself, “Am I doing an impressionistic watercolor of the flute’s sound, or am I trying to create a photorealistic oil painting complete with as many details as I can pack into it?”

Once you’ve completed the sound, you’ll want to play a part that is idiomatic to that instrument. For example, if you’re using a Japanese flute that mostly embraces a pentatonic scale, then playing a hot blues riff would not help your emulation sound authentic.

Producing realistic sounds often means applying multiple sound-creation techniques to define different aspects of the finished sound. If we stay with our flute example, then the initial attack might be a sample, and the sound’s “body” or sustain might be from an analog synth; the key clicks might be from a digital synth, and the release might be another sample.

Depending on the part, you could combine instruments by chaining apps, stacking instruments over MIDI, or playing different aspects of the sound separately, so that you have more control over level and timing. If you’re crafting timbres that have a lot of detail to them and those details happen after you trigger the note initially, be prepared to fine-tune your wind noise, note bends, and releases to get the overall performance you hear in your head. When emulating instruments, ultimately, you are constructing a believable performance as well as a great sound.

In a World…

When you’re emulating sounds from nature, consider that simply recording a sound happening out in the world may not work in the way you want. A huge factor is deciding what the sonic world of your piece, film, or video will sound like. Like a production designer, you create your project’s sonic world, and the sounds you make conform to that world.

For example, let’s say you’re working on a television commercial and there’s a scene of a leaf falling from its branch to the ground. Is it a gentle leaf? Did a breeze make it fall? What time of year is it? Will the geographical location affect how you create the sound? Is this an intense leaf that could be foreshadowing action later in the ad? Sound designers ask these and other questions, so always be inquisitive.

Sound can give inanimate objects personality. When working on Star Wars, legendary sound designer Ben Burtt gave the droid R2-D2 a personality, a voice, and even a soul by integrating his ingenious use of an ARP 2600 synthesizer with his own processed voice.

Trial and error is often the key to creating new sounds. For the best results, you need to be patient with the process and masterful enough with your gear to squeeze every possibility out of it. Stumbling around in the dark, guessing at how your synth, processor, or app could affect the sound you’re making might net you a surprising result, but not the result you need. When you just stumble onto a sound, you may not know how to replicate it or tweak it when the producer or film company asks.

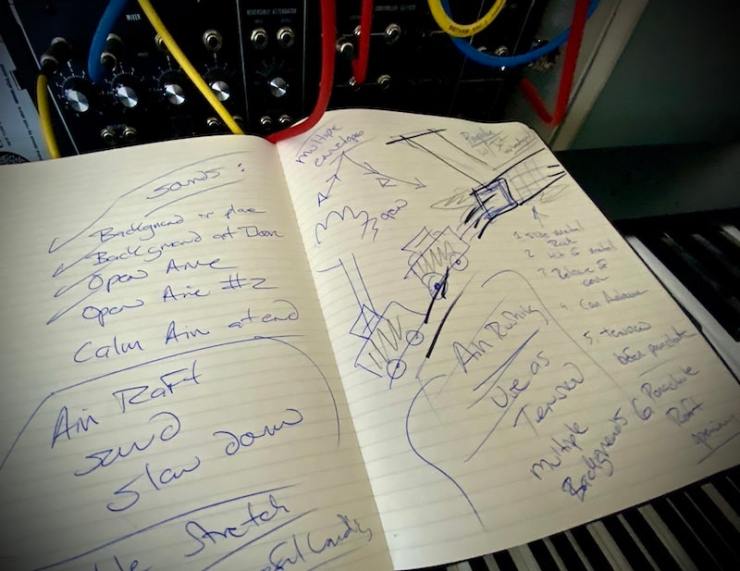

Know your gear. Be adventurous. Take notes on how you make sounds. My sound design journals go on for hundreds of pages.

Communication Is Key

When deciding what your sonic world will sound like, the single most crucial element is communication. So many of my genius composer and sound designer friends are terrible at communicating, and their work is cast aside or overlooked when the production heats up. In some cases, you need to be ready to defend your choices and explain how your sound fits in with the creative brief or with the conversation you had with the artist.

You have to be willing to collaborate and communicate about the sounds you make, especially on TV and film projects, because sound defines the third dimension of so many scenes in movies. On music projects, being in communication with the artist, producer, and even the label is crucial, particularly when you’re trying to create a new sound and take a new approach. The critical factor is that no one knows how your project is going to turn out. Therefore, be collaborative, be humble, and listen more than you speak, especially with clients.

Many people are afraid of doing something new and different. Consequently, you need to tread carefully when you’re presenting your work to assure them that the huge jet engine sound you just cut in against their falling leaf will work in context and transmit the message that the advertisement is trying to convey.

One Final Thought

You need to listen to a lot of great sounds to get a sense of whether your new sound is actually new or someone else made the same sound 15 years ago. Knowing what other people have already done is important. Many composers don’t listen to other people’s music because they are afraid it will affect their compositions, and I understand that. However, in sound design, you need to know the history and why Walter Murch was important. And if you don’t know who he is, Google him.

Sound design will go as deep as you want to go. Sometimes I spend months designing sounds. On my new album Sacred Spaces, I spent nearly four months designing more than 800 sounds from dozens of different sources. On my song “Devotion,” for example, I created a rhythm made up of processed vocal samples assigned to random pitches and randomized note groupings. Sometimes when you build textures and sonic material, they only need to be deployed creatively to be unique and fresh. I know you will create your own workflow and processes, and I hope this article has helped you shape them. Happy creating!

Look here for more on Michael Whalen.

-

In This Issue4 weeks ago

Native Instruments Kontakt 7 Is Now Compatible With macOS Sonoma

-

Covers3 weeks ago

Image-Line FL Studio 21.2.3: the Synth and Software review

-

In This Issue3 weeks ago

New From Orchestral Tools, Monolith by Richard Harvey

-

In This Issue2 weeks ago

New Chromaphone 3 and AAS Player Plug-ins